In the humid Kenyan heat, the makeshift trail ran through villages and towns in the middle of a forest. One casual, run-of-the-mill Sunday, a weekly running group was completing a half marathon. I was one of the many participants. By the tenth kilometer, I could feel my calves constrict as they often do. “This is ok, I can manage,” I thought. At the fifteenth kilometer, my legs were aching, and I turned to self-talk as I climbed like a mountain goat up a small hill.

As sweat and pain washed over my body and the phosphorous-rich soil colored my shoes red, I kept thinking about the finishing line, visualizing the feeling of crossing it, and without much fanfare, made it to the end. Upon reflection, the experience was painful yet fun and challenging and – if my memory does anything right – romanticized what most people would call a “No, thank you” experience.

Stories of struggle and perseverance are captivating because they present a view that pits the individual against nature, or the individual against the many, or the I against the self. It is the triumph of will that stirs in us the drive to do something. David Goggins, in his second memoir-cum-self-help book, captures this triumph of the will like no other.

The memoir starts with the success of his previous book, Can’t Hurt Me, and documents the impact of success on his life. How his transition from a “savage” to a “part-time savage” irks him and motivates him to restart his journey, put his running shoes back on, and enter a cave of pain, once more.

“Oh, I looked the part. I was ripped, and if you tried to run with me, you’d come away thinking that I still had it. But even though I worked out twice a day, I was a part-time savage at best, a glorified Weekend Warrior.”

Never Finished: Unshackle Your Mind and Win the War Within

As one reads the memoir, Goggins discusses the different tips and tricks that helped him achieve his goals. For instance, he talks about a “mental lab,” which is a meeting with oneself about how you are getting on with your goals or your life, in general. Goggins’s prescriptions are particularly incisive because this “medicine” is something he’s consumed himself. This is to the attraction of Goggins – that he has developed these ideas through personal experience. The sine curve of his life resonates with many. Goggins wasn’t always an ultra-marathon runner or someone who could read. Yet, he toiled to change how he felt about himself and how he saw himself in the mirror every morning as he shaved his head (Goggins is bald).

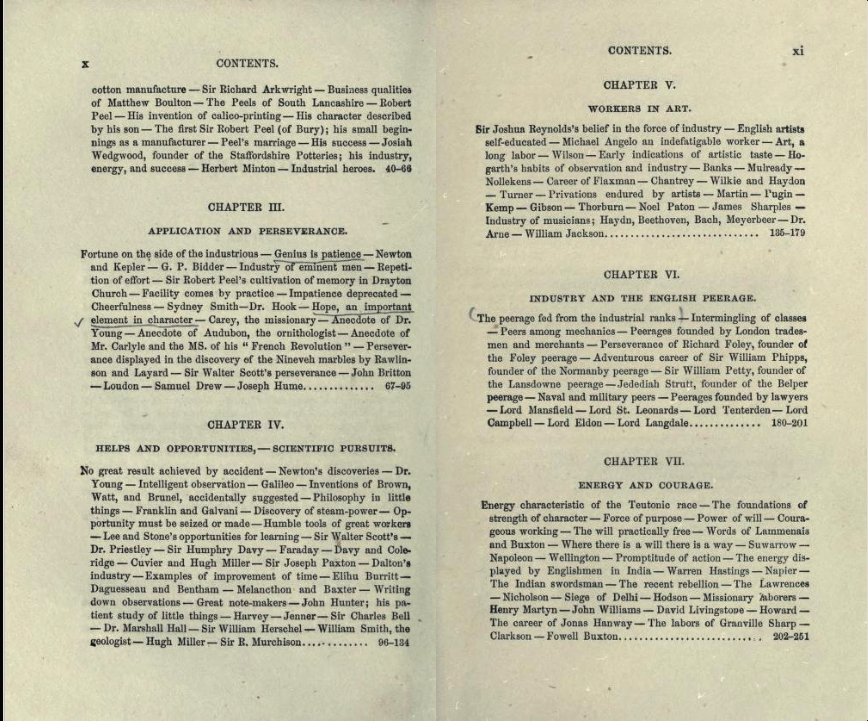

A Brief History of Self Help

The self-help genre came into prominence in the mid to late 1800s and, in fact, the word itself comes from Self-Help by Samuel Smiles (first published in 1859).

The origins of self-help are not precisely Victorian London (however, one wonders why industrialized Victorian London and not another place). The notion that one can change oneself through action or building one’s character goes as far back as Xenophon (The Education of Cyrus), if not further. Earlier books in a similar vein were called “Mirrors-for-Princes.”

The aristocracy used these books, typically written by diplomats or tutors, to educate their children. The idea was that if one has good virtues (whatever those might be), then one would grow to be an effective or good person. Some examples are the Panchtantra by Vishnu Sharma, written around 200 BCE, and The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli, written in the 16th century.

Fast forward a few hundred years, past Poor Richard’s Almanack (also a self-help book, although some would protest its inclusion), to the early 1920s when Napoleon Hill wrote the much lesser known The Law of Success, followed by the genre-defining, Think and Grow Rich.

Many subsequent self-help books draw on the same philosophy as Think and Grow Rich without explicitly mentioning it. For instance, many self-help books recommend “positive thinking” or generally, the notion that thought dictates action and feelings, etc.; by simply thinking that one can, one will.

Goggins is in direct contrast to this idea.

The Last 100 Meters

Goggins routinely highlights in his memoir, as well as in interviews, “You have to suffer,” and you must put yourself in a position where you can reflect and manage your pain. The lessons, he contends, you learn while you’re in pain are ones you will keep forever.

Throughout the memoir, Goggins highlights painful moments such as his torturous 100-mile run in Leadville, his lessons from that experience as well as his traumatic childhood. There is hardly a sentence or paragraph, much less a section, which casts doubt on his story or his prescriptions.

This makes Never Finished a page-turner, a helpful guide, and an emotional story. Everything is 100% real. It’s the same reason why a ’90s Jackie Chan movie is more impressive than every action movie in the last five years. When Jackie jumps from a roof, it’s him. He risks everything for a single take, as does Goggins in his memoir. He lays it all bare, points out his lessons for you to try, and says, “Merry Christmas.”